Know Your Problem: Strategizing in Complexity

Not all problems are created equal.

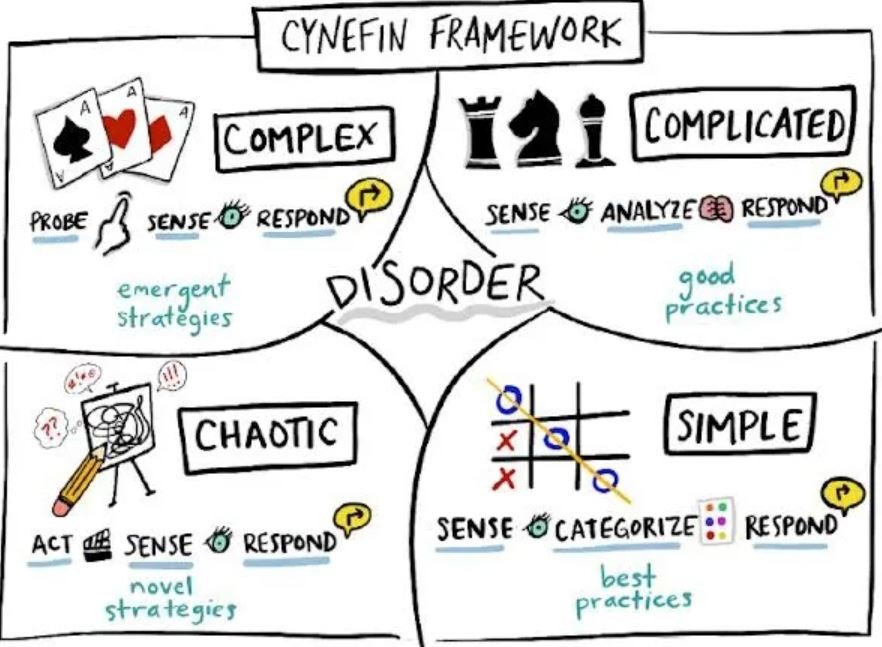

That doesn’t mean they are any less worthy of solving, but it does mean our approach and strategy need to match the nature of what we’re up against. To help us consider the relationship between the nature of problems and strategy, we often refer to the Cynefin Framework.

The Cynefin Framework

The term “Cynefin” (pronounced “kuh-NEV-in”) is a Welsh word that roughly translates to “habitat” or “place” in English (for a more extended definition, I invite you to a cup of tea with my Welsh wife). Here, we use it in reference to a conceptual framework created by Dave Snowden to assist organizations and individuals in understanding the nature of the problems they encounter. The framework divides problems into four distinct domains: Simple, Complicated, Complex, and Chaotic.

Image credit: GovCrate

Simple and Complicated Problems: Predictable cause and effect

Simple problems are straightforward and predictable. For example, baking a cake. If we put the same ingredients together, time and again – flour, butter, eggs, sugar – and place them in a predictable environment – an oven set at 350 F – we can expect to get more or less the same outcome. The cause-and-effect relationship is clear.

Complicated problems become more – well, complicated – but they are still acting in environments that are mostly predictable. NASA engineers, for example, can acquire the knowledge needed to build and launch a spacecraft by mastering and combining disciplines. Despite the level of specialized knowledge required, under known conditions, these problems also yield consistent outcomes. In both simple and complicated problems, the knowability of cause-and-effect relationships allows for standardized solutions, often with expert knowledge required as we move toward the increasingly complicated.

Chaotic Problems: A brief glimpse into mayhem

The Chaotic domain, where cause and effect are totally elusive, requires a completely different approach. This territory is characterized by war, natural disasters, or other extreme crises. Here, an immediate, crisis response is required rather than strategy.

Complex Problems: Hard to pull apart

In complexity, problems are influenced by numerous variables – some of which are not fully understood – meaning that cause and effect are hard to pull apart. We can’t be quite sure that X will lead to Y. It might. But there might be other forces at play, other interdependencies pulling at our problem that we hadn’t fully understood. This is the nature of problems often captured in our VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous) world.

The most common example is that of raising a child. You can provide a set of more or less consistent outputs, and try to keep the environment the same, but the outcome is never fully predictable. In the realm of our work, examples of complex problems include the housing and affordability crises, climate change, and poverty reduction, to name a few – problems where social, economic, political, and psychological factors collide in unpredictable ways.

Strategizing in Complexity: Four Lessons

It might seem that strategizing in complexity is a futile exercise – but that’s far from the truth. Strategy remains critical in complexity because it guides our choices and actions, even when the path isn’t linear or predictable. Our work happens primarily in the domain of the complex and I want to share four lessons we’ve learned from facilitating strategy in these challenge spaces:

Embrace the nature of your problem: Don’t deny the nature of your problem space. If you’re working in complexity, resist the temptation to treat it as a ‘complicated problem’ with predefined solutions. Complex problems reject one-size-fits-all solutions. Start with that recognition.

Make decisions collaboratively: Complex problems are multifaceted and require input from a diverse range of perspectives. There is no single “expert” who can unravel the issue alone. Instead, tap into collective intelligence, draw insights from various angles, and embrace divergent thinking as a strength, not a challenge.

Experiment and iterate: To navigate complexity, we need an atmosphere of experimentation and iteration. Getting it ‘right’ on our first try is unlikely. We need to treat the work as a continuous learning process and an act of strategic refinement and adaptation as we go. As conditions change, so should your approach.

Use different levers at different times. Recognizing that complex problems don’t adhere to linear, cause-and-effect principles, we must strategize in equally dynamic ways. This means that changing environments call for different levers. Advocacy might be the most strategic move in one scenario, while in another, leaning heavily towards fundraising or investing in research might take precedence. Flexibility and context-driven decision-making become essential tools when dealing with complex problems.

It’s clear that understanding the nature of your problem isn’t an optional step – it’s a critical starting point for developing effective strategies. We urge you to consider, what’s your problem? And how can you embrace complexity to navigate the way forward.